By Oliver Behr and Karl Luis Neumann

Energy improves safety, security, productivity, and health in refugee settlements. Considering the environmental impact, solar energy is a key technology to establish clean and sustainable long-term energy supply in displaced settlements. Although access to solar devices has increased in recent years, their long-term operation and maintenance are often overlooked. This report takes a market-based view to develop a voucher system that facilitates the transition to a sustainable use of solar energy at refugee camps while fostering the economic inclusion and empowerment of refugees.

Refugee camps transition to clean, renewable energy

One person becomes displaced every 2 seconds — less than the time it takes to read this sentence. Worldwide, there are at least 71 million people who have been forced to flee their homes. Nearly 26 million people have crossed national borders and are not able to return home safely. These concerning figures have steadily increased over the last years and will likely continue to do so with climate change and armed disputes putting further pressure on the global community.

While the majority of refugees reside in urban settings, there is a large number of refugees that live in managed refugee camps — or displacement settlements — which are mainly located in the global south. For most of these refugees, displacement is not a temporary experience. Almost half of all current refugees have been displaced for over ten years and remain in displacement settlements for an average of 17 years.

In light of these developments, the role of humanitarian agencies such as UNHCR and its implementing partners has evolved significantly. In addition to the provision of short-term, temporary emergency relief, they need to manage the displacement camps following a long-term strategy.

To ensure the situation in displacement settlements is working and improving in the long term, energy access is particularly important. Effective energy distribution relates to all camp activities and basic necessities: pumping and treatment of clean water; heating; cooling for food storage; cooking; energy for livelihood and economic activities; and provision of light for schooling, hospitals, and the prevention of violence against women and children. Based on these significant beneficial aspects, most experts agree that energy access in these camps is a basic need and key to overcoming poverty, increasing livelihood, and resolving environmental degradation. However, most displaced settlements lack such basic energy supply as they are often not connected to the national energy grid of hosting countries.

Therefore, these off-grid camps predominantly rely on decentralized fossil-based energy sources, such as diesel generators which are highly unsustainable both from an economic and environmental perspective. UNHCR has recognized this and launched a Sustainable Energy Strategy in response which promotes the transition to clean energy in the humanitarian context.

On-site solutions, based-on renewable sources are increasingly available and affordable, as well as clean and climate-safe. In recent years, humanitarian agencies, social startups, corporations and NGOs have started to introduce solar-based systems into the camps, wherever the environmental conditions are favorable for the use of solar systems (e.g. Sub-Saharan Africa). For example, big solar panels are used in combination with diesel generation to form a mini-grid that supplies camp-wide infrastructure, such as water pumps, streetlights, and social institutions. Additionally, many households have gained access to smaller solar systems that enable them to electrify their homes. Examples include solar lanterns that allow camp inhabitants to light their shelters or to charge mobile phones.

A considerable number of such devices originate from donors and are distributed by NGOs and humanitarian agencies to households, often without a charge. However, simply donating such devices has discouraged the establishment of an operation and maintenance infrastructure. As long as new devices are distributed for free, there is no incentive to handle donated devices with care or to repair them. Therefore, camp authorities and humanitarian agencies started to promote market-based structures in displacement settings. These include new ways of delivering energy devices to households through market-based mechanisms (solar devices for purchase, e.g. Payasyougo business models).

The problem: Insufficient technical knowledge about solar devices and limited repair infrastructure

Looking at automobiles is worthwhile to understand why market-based approaches are particularly important in the context of solar energy systems. Whenever a car breaks down somewhere around the world, car owners can either apply quick fixes themselves or get support from a local expert. Such car repair knowledge and infrastructure can be found throughout the world, given the economic attractiveness of running such repair shops. This enables people to operate and maintain cars nearly everywhere around the globe.

Such infrastructure is not available for solar devices, particularly not in displacement settings. Today, humanitarian actors in displacement settings are largely concerned with the procurement and distribution of solar devices, not with operating and maintaining them. As a result, knowledge about the operation and maintenance of solar devices is rare, and repair infrastructure overwhelmingly does not exist. This lack of knowledge and infrastructure originates from the missing system-thinking (only procurement) and a lack of market-based approaches to distribute solar devices. This is a key challenge towards a sustainable solar energy system in displacement settings which specifically affects households in the camp. They often receive or purchase new solar devices, but do not receive any operations and maintenance support. As a result, the incorrect use of solar devices is common and households are often left with broken devices. This is further complicated by the household’s low disposable incomes and the limited resources they can spend on repair work.

Altogether, this leads to a reduction of the developmental and social impact solar devices could potentially bring about. Most experts and scholars agree with the fact that while humanitarian organizations have increased the deployment of renewable energy systems to support infrastructure in refugee settlements, more attention to proper operation and maintenance is needed to fully capitalize on the benefits. This leads to the question of how to set up a system that fosters the transfer of solar device-specific technical knowledge to displacement settings while encouraging economic repair activity and infrastructure at the same time.

Establishing a solar repair voucher system

One possible solution to this challenge is a voucher-based system deployed by humanitarian agencies. Such a system

- incentivises the use of solar devices and the accumulation of technical knowledge about solar systems while it

- subsidises the establishment of solar repair shops and promotes knowledge diversification of existing repair shops.

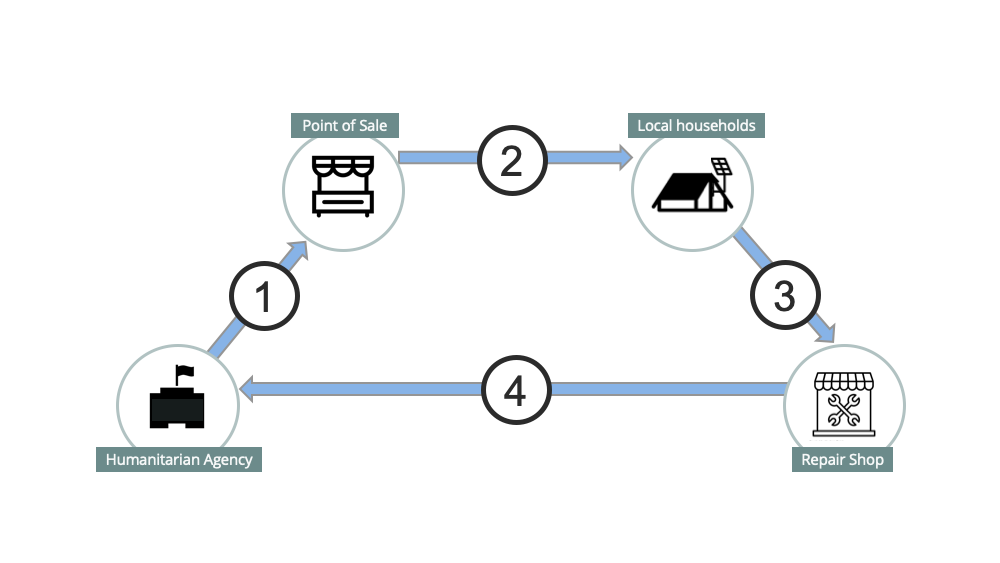

On a high level, such a system involves four stakeholders:

- humanitarian agencies such as UNHCR and its implementing partners,

- point of sales (PoS) of solar energy devices such as kiosks,

- local households in the camps and surrounding areas, and finally

- repair shops (newly founded or existing).

The proposed system fundamentally consists of a repair voucher, which is created and distributed by the humanitarian agency. This voucher circulates between the four stakeholders. It thereby incentivizes the accumulation of technical knowledge (solar device infrastructure) and subsidizes the establishment of solar repair shops (economic activity).

(1) Relationship humanitarian agency — point of sale

The humanitarian agency creates repair vouchers (physical or digital), where each voucher is connected with one particular solar device. This repair voucher is solely designated for the repair and maintenance of its respective solar device. Therefore, the humanitarian agency should set up a database that connects each solar device (solar device ID) that arrives at the displacement setting with its repair voucher (repair voucher ID). To initiate the system, the humanitarian agency should distribute the vouchers to the point of sales and update the database accordingly. Now, each solar device that is for sale in the settlement has a repair voucher connected to it.

(2) Relationship point of sale — households

Whenever a household purchases a solar energy device at a point of sale, it will receive the voucher on top of its purchase (either free of charge or for a small fee).

Once the household’s solar device breaks and requires maintenance or repair, they will demand a repair activity. Steady demand from households for solar device repair works has been created.

(3) Relationship households — repair shop

This demand for device repair works can now be served by solar repair shops (demand meets supply). Once the solar device is broken, households take their device to local repair shops and exchange the repair voucher against repair and maintenance services.

(4) Repair shop — humanitarian agency

Besides handing out the repair vouchers to create a demand for repair activity, the humanitarian agency stimulates the repair supply side by providing training to repair shops, mechanics, and entrepreneurs in the camp (operation and maintenance of solar energy devices in cooperation with the device manufacturers). Those repair shops and entrepreneurs can offer their solar repair services to the households that hold repair vouchers. Training can increase in scope and complexity over time to diversify the knowledge of repair shops even more.

The driving factor of this system is the monetization of the repair voucher in the relationship between the repair shops and humanitarian agency. Once the repair work has been completed, the repair shop takes the voucher to the humanitarian agency and will be reimbursed for its repair activity. The value of this voucher can be anything from one-time repair work to a monthly repair allowance.

Regardless of their form, vouchers that can be exchanged for money create an economic incentive to set up repair shops. Essentially, the vouchers are low-hanging fruit for repair shops which just need to be reaped.

Finally, the voucher has circulated amongst all stakeholders and consequently,

- ensured that solar energy devices get repaired,

- increased solar device-specific knowledge in the camps,

- created demand for solar repair activities and

- provided a reliable basic income and training for solar repair shops.

This overview only scratches the surface of a self-supporting, economically viable solar system in displacement settings, and needs to be adapted to the different circumstances in specific camps.

Transforming the system into a self-sustaining market

Taking this overview as a basis, it is important to discuss exit scenarios for the humanitarian agency, in order for the system to transform into a self-supporting economic environment.

One option to do so incorporates solar device manufacturers, energy-as-a-service or Payasyougo providers. These actors are striving to enter the local market of displacement settings. However, they face difficulties to bring devices, repair infrastructure and spare parts to the camps. This is critical, as guarantee claims or their business model requires them to ensure that the solar devices operate effectively and are repaired and maintained.

Therefore, a possible exit scenario is to replace the humanitarian agency with such an actor (or group of actors), who is then responsible for issuing repair vouchers, providing training, and compensating local repair shops.

In a subsequent step, the repair vouchers could become redundant and can be substituted by traditional money exchange. Repair shops can be upgraded to repair contractors of the solar device provider, which provides them with a steady source of income. The costs for repair and maintenance activities are then included in the monthly installment of customers without being facilitated by a voucher.

A critical limitation to this system can be seen in the access to spare-parts, as numerous different solar energy devices exist from several manufacturers, with different levels of quality, repairability, or spare-part access. In addition, there is potential for fraud or misguided incentives in this system, such as repair shops declaring higher repair costs than their actual expenditure. Such challenges should be considered and solutions should be tested and incorporated.

Conclusion and next steps

We introduce and advocate this solution for two reasons. Firstly, creating a voucher-based system is in line with current practice and experience (vouchers and training) of the camp’s stakeholders. Hence, this approach is relatively easy to implement into existing environments in displaced settings. For both stakeholder groups, humanitarian agencies and local communities, the approach is related to their experiences and, therefore, potentially enjoys high acceptance.

Secondly, although the costs associated with this approach are high, long-term benefits are profound. In addition to employment for repair shop operators, knowledge and skills regarding solar energy devices increase in the settlements. As solar systems aspire to become the dominant source of energy, establishing adequate infrastructure and knowledge in terms of operation and maintenance is essential. The voucher system can stimulate this through economic incentives that encourage a self-sustaining system in the long run.

We want to initiate a discussion of how market-based approaches can ensure sustainable energy supply in displaced settings. Applying economic concepts and system thinking approaches is crucial to set up a system that fosters the establishment of solar-based energy solutions in the long run. Based on economic incentives, the described voucher system can be one step that leads to increased access to sustainable energy for displaced populations.

This article was originally published on Medium, on May 27, 2020, and republished with permission.